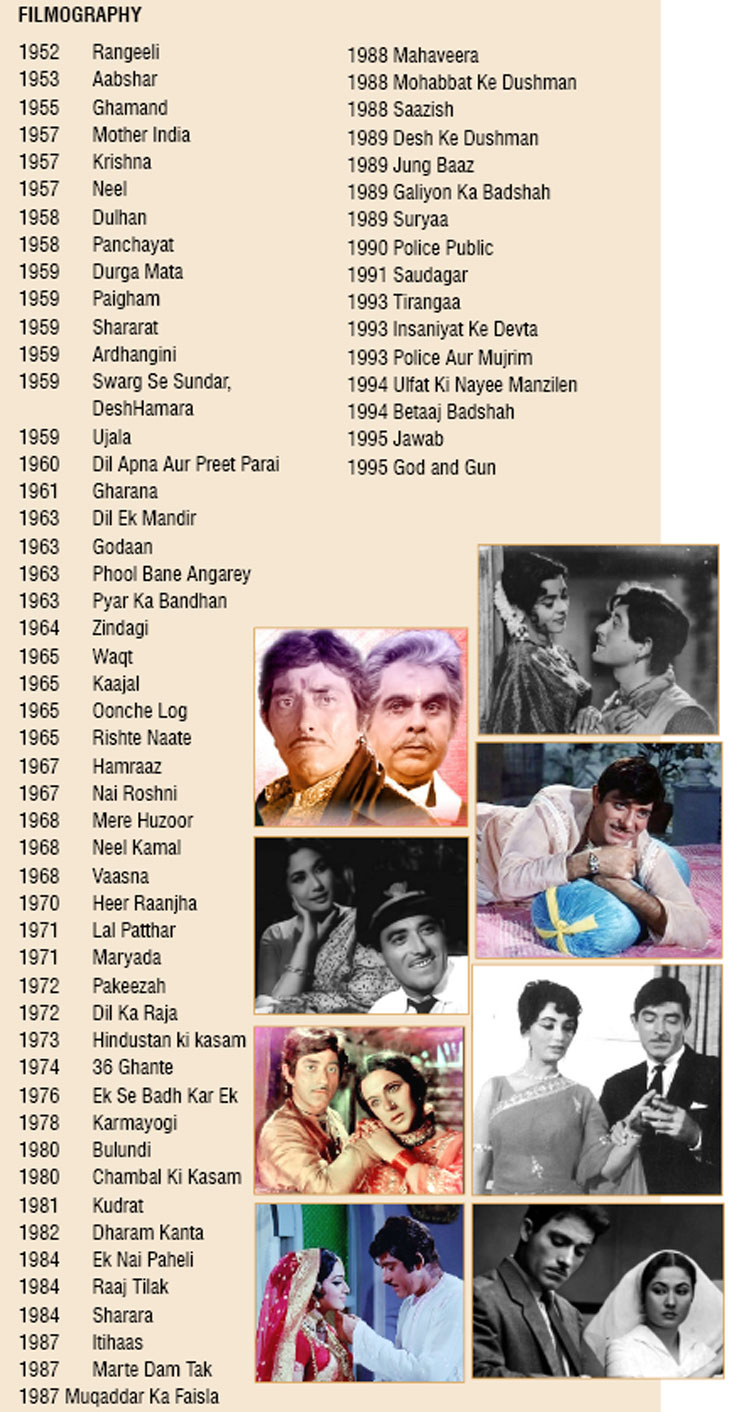

Raaj Kumar “Remembering The Wit And Eccentricity Of Raaj Kumar”

The story goes that it was the great Sohrab Modi who spotted Raaj Kumar at the Metro cinema, then owned and run by the powerful Hollywood studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, in Bombay. Captivated by the tall, sharp-looking man, Modi offered him a role, only to be turned down.

To put that in context, Sohrab Modi in the 1950s was like Yash Chopra in the 1990s, a titan of the film industry. It was a sign of Raaj Kumar’s self-belief, integrity and, as some would call it, pride that he turned down one of the biggest directors of the time.

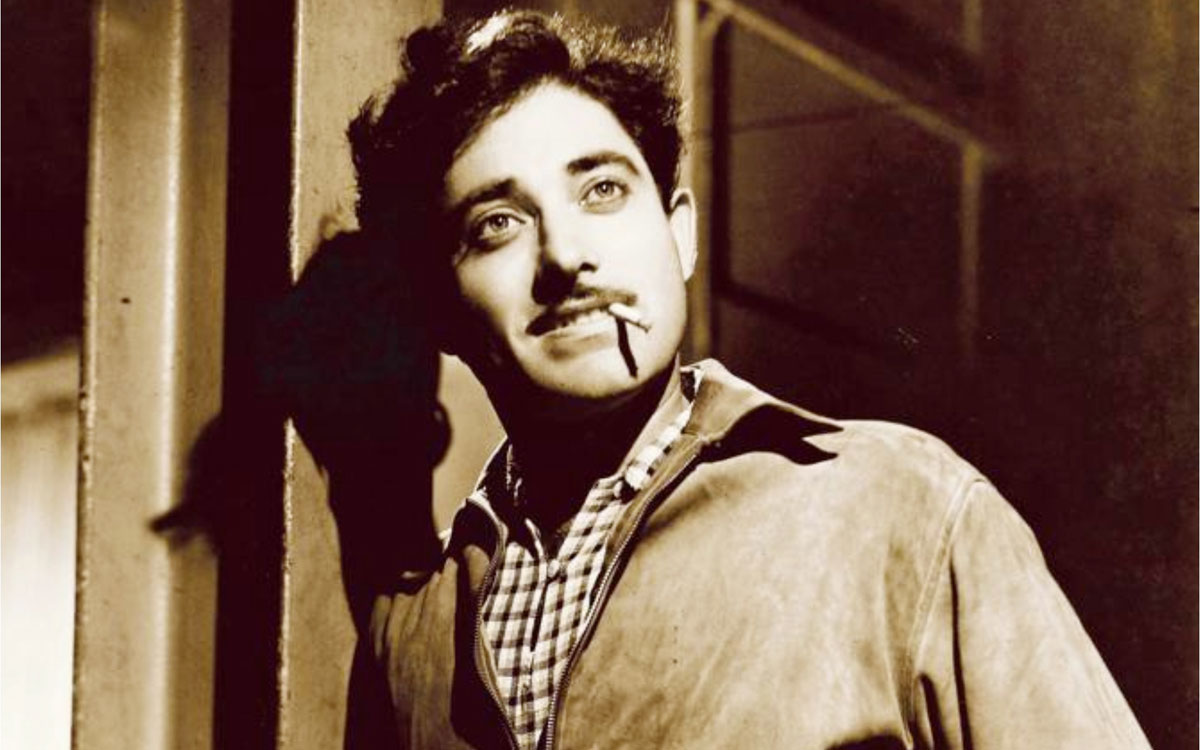

This incident is one of many that mark out the actor’s eccentric and enigmatic personality. Born in a Kashmiri family as Kulbhushan Pandit in 1926, the actor moved to Bombay having cleared the civil services examination. He joined as a sub-inspector at the Colaba branch of the Bombay police. However, his style, grace, and charm eventually led him down the path of films.

This incident is one of many that mark out the actor’s eccentric and enigmatic personality. Born in a Kashmiri family as Kulbhushan Pandit in 1926, the actor moved to Bombay having cleared the civil services examination. He joined as a sub-inspector at the Colaba branch of the Bombay police. However, his style, grace, and charm eventually led him down the path of films.

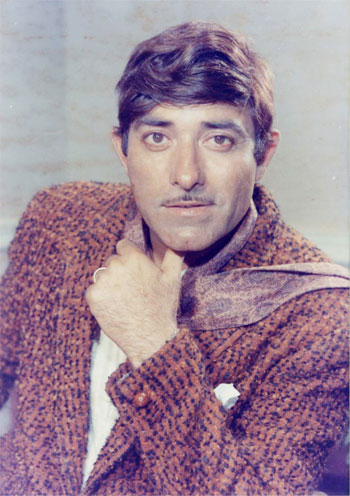

Making his debut in Rangeeli (1952), the actor went on to deliver iconic performances in films like Dil Ek Mandir (1963), Waqt (1965) and Mere Huzoor (1968), among others. These films established him as a unique star outside the romantic hero template exemplified by Rajendra Kumar, Shammi Kapoor, Shashi Kapoor and Dev Anand.

In an article in Cine Blitz magazine in 1996, when Raaj Kumar died of cancer, veteran director BR Chopra had said, “As an actor he was an absolute delight to work with. He was totally a director’s actor who put in that extra little something which only belongs to the greats. The only little difficulty that takes place is right at the begin¬ning. He needed exactly 48 hours to discuss the script with the writers. If he was satisfied with the role, he would sign on immediately. He always needed to be approached properly. He always arrived well prepared and was most punctual. When I heard about his problems with other directors, I used to chuckle to myself. They must have allowed themselves to be taken for granted.”

While Raaj Kumar was a natural at his craft, it was his life outside the craft that fascinated people. Well-read, a florid orator, and a gentleman, Raaj Kumar was often known for his spontaneous, eccentric behaviour. As the actor himself said in a Stardust magazine interview in 1972, “I believe in things I do, I do things I believe in.”

The statement captured the confidence and measure of the man. A legendary wit, he is said to have once told Zeenat Aman, who was at her peak in the 1970s, “You have a pretty face. You should try acting.”

At another time, he walked into Rajendra Kumar’s studio and upon finding a large photo of the star hanging by the entrance remarked to the attendant in his inimitable style, “Jaani, ye chale gaye, aur tumne hamein bataaya bhi nahi? [Darling, he passed away and you didn’t even inform me?]”

BR Chopra said, “Different people hold different opinions [about him] and I think he did that deliberately. I always got the impression that he dealt and talked to people with a bemused attitude, as though he had an ace up his sleeve… He liked up¬right, confident people and was nobody’s fool. He could imme¬diately see through any kind of sycophancy. Personally, I think he was a very misunderstood person, mainly because of his bluntness.”

BR Chopra said, “Different people hold different opinions [about him] and I think he did that deliberately. I always got the impression that he dealt and talked to people with a bemused attitude, as though he had an ace up his sleeve… He liked up¬right, confident people and was nobody’s fool. He could imme¬diately see through any kind of sycophancy. Personally, I think he was a very misunderstood person, mainly because of his bluntness.”

But to consider such savoir-fare as a sign of nonchalance was a mistake. Despite his image as a commercial actor, Raaj Kumar was also a keen watcher of arthouse cinema. A proof of that is the anecdote about him calling up director Mani Kaul after the release of Uski Roti (1971) and telling him, “Jaani, kya art-vart film banaateho, Uski Roti. Hamaarepaaschaleaao our commercial film banaate hain Apna Halwa.” That a man, now lampooned for his over-the-top style, knew and watched Mani Kaul’s film is a sign of his mysterious personality.

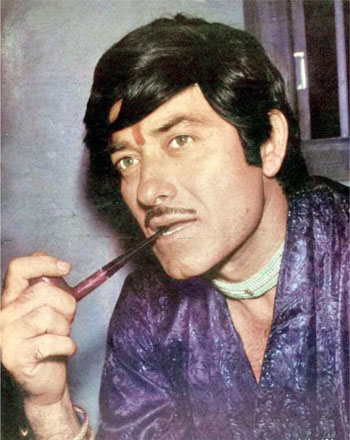

His fashion remains a topic of great mirth for the internet generation. From purple velvet suits to collar bands, the actor sported a wide variety of styles that can only be defined as unique. However, he could say, as the designer Coco Chanel did, ‘I don’t do fashion, I am fashion.’

The actor passed away on 3 July 1996 after a tiring battle with throat cancer. Even in his last days, he remained as he was. Resolute and adamant. When director Subhash Ghai paid the ailing actor a visit, Raaj Kumar is said to have remarked, “Raaj Kumar ko bi maari hogi toh badi hogi na, koi zukaam se thodi na marega Raaj Kumar. [Even Raaj Kumar’s sickness has to be grand, he isn’t one to die of a common cold.]”

Puru Raajkumar

A whistling train dissolving into the brooding night, a slumber-kissed Meena Kumari cradled in it. A stranger, a co-traveller, mesmerised by her exquisite feet leaves behind a note, which reads, “Aapke paon… bahut haseen hain. Inhe zameen pe mat utariyega. Maile ho jaayenge!” Even 40 years later, the dialogue rendered by the late Raaj Kumar in Kamal Amrohi’s classic Pakeezah (1972) is listed among Hindi cinema’s most romantic moments. And to think that the actor once served in the police force. That perhaps explains the inadvertent undertone of authority that crept into his dialogue delivery. “My father had strong language skills. Born as Kulbhushan Pandit in Loralai, Balochistan (now in Pakistan) into a Kashmiri Pandit family, he could write and speak Urdu,” comments son and actor Purru Raaj Kumar on his father’s formidable dialogue delivery famously prefixed with a ‘Jaani!’

Just as forceful were his on-screen portrayals in over a 100 films like Mother India, Waqt, Heer Ranjha, Saudagar and Tiranga, his off-screen person was as quirky, be it his wacky fashion sense or outspokenness. If the paparazzi went berserk shooting him in brocade shirts and outlandish footwear, the media had several stories about his unapologetic (and often embarrassing) run-ins with his peers. For instance, he allegedly refused Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer because he didn’t like ‘the director’s face’. On another occasion, he supposedly told Zeenat Aman that after Satyam Shivam Sundaram it was difficult to recognise her with her clothes on.

Just as forceful were his on-screen portrayals in over a 100 films like Mother India, Waqt, Heer Ranjha, Saudagar and Tiranga, his off-screen person was as quirky, be it his wacky fashion sense or outspokenness. If the paparazzi went berserk shooting him in brocade shirts and outlandish footwear, the media had several stories about his unapologetic (and often embarrassing) run-ins with his peers. For instance, he allegedly refused Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer because he didn’t like ‘the director’s face’. On another occasion, he supposedly told Zeenat Aman that after Satyam Shivam Sundaram it was difficult to recognise her with her clothes on.

“My father was a moonhphat (outspoken) though I’ve no clue about this incident with Prakashji. But it’s believable. Dad did have a wicked sense of humour. But no ill-intent,” smiles Purru. “My father may have been bizarre but he was never boring. They don’t make stars like him anymore,” says Purru, as he goes into flashback mode.

Growing Up

My first memory of my father was when I was a couple of years old — leaping from my mother’s arms into his. I also vividly remember the two-and-half-month long summer vacations that we — Amma (mother Gayatri), Abba (I also called dad, papa or bauji), my younger brother Panini and sister Vastavikta — enjoyed in Kashmir, year after year, right up till 1987. There would be a stopover in Srinagar and then we’d proceed to Gulmarg and Pahalgam where we stayed in a log house.

We’d play golf, go horse riding or play table tennis during the day. Dad would go for treks with mom. In the evening we’d have barbeques. I remember I was 14, when dad threw a party to celebrate mom’s birthday. Friends from Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai and Gulmarg trooped in — around 200 people. There was song and dance. Dad enjoyed classical music and ghazals. He’d keep playing Aye dil-e-nadaan (Razia Sultan) and the valley reverberated with the melody.

For dad, the most beautiful woman in the world was my mother. She was an airhostess and they met on a flight. The romance blossomed and they got married (during the 60s). An Anglo-Indian, her original name was Jennifer. She was later renamed Gayatri according to her kundli. Basically, we’ve been brought up in all faiths. We’d visit churches, dargahs, mandirs and synagogues.

Our childhood was spent in a bungalow at Worli Sea face. We studied at Green Lawns School. When our house was being painted, we shifted to our Juhu bungalow for a while. Dad would drive us to school in Worli in his Chevrolet. My parents pampered us but never spoilt us. It was not like you’ll get everything in the toy shop. And even though dad was kadak (disciplinarian) there was no pressure on us to be A-graders. Rather, he encouraged us to engage in outdoor activities, reading and the fine arts. He got magazines like National Geographic and Reader’s Digest. It was not to make us intellectual but aware. We weren’t affected by his stardom. It was not like you raised your hand and the staff came running, saying ‘Jeesaab!’

Our childhood was spent in a bungalow at Worli Sea face. We studied at Green Lawns School. When our house was being painted, we shifted to our Juhu bungalow for a while. Dad would drive us to school in Worli in his Chevrolet. My parents pampered us but never spoilt us. It was not like you’ll get everything in the toy shop. And even though dad was kadak (disciplinarian) there was no pressure on us to be A-graders. Rather, he encouraged us to engage in outdoor activities, reading and the fine arts. He got magazines like National Geographic and Reader’s Digest. It was not to make us intellectual but aware. We weren’t affected by his stardom. It was not like you raised your hand and the staff came running, saying ‘Jeesaab!’

As an adolescent, I remember having inane arguments with him. I’m hot-headed too. It’s a genetic trait. Like he’d ask me, ‘You want to play golf?’ I’d say, ‘No!’ He’d retort, ‘Why?’ I’d shoot back, ‘I don’t feel like!’ He’d fume, ‘That’s not how you talk to your father!’ But actually he was soft at heart. When he came to drop me at college in the US, he began crying. I thought, ‘What’s wrong with him? I couldn’t imagine a larger-than-life figure like him in tears!

Dad and Mom

Dad was a romantic. He sought romance even in the smallest things — like driving in his jeep with mom to have paan at Peddar Road. They also enjoyed watching TV or reading a book together. They’d debate on even what to make for lunch. And when she’d cook something, she’d wait for him to compliment. But he’d be busy eating. Then hours later, looking into nothingness, he’d say, ‘What you prepared today was delicious’.

It would have been natural for mom to be insecure, dad being the star he was. But she never shared any such feelings with us. I can’t say why she never accompanied him to public events. Maybe she wasn’t comfortable. He never gifted her on occasions. But it would be a surprise, like a holiday.

What He Liked

What He Liked

Dad began his day with kahwa, a Kashmiri drink, made with black tea, honey, almonds and tulsi leaves. On off days, lunch and dinner would be with the family. Being a Kashmiri Pandit, he loved rogan josh, chaman (paneer) with baingan and kasuri methi. He also enjoyed continental food. At times, he cooked and sometimes we’d catch him in the kitchen stirring the kheer. He enjoyed methi parathas for dinner, which was at 8 pm. He was a light eater and remained fit because he was a golfer. He did horse riding at the Old Amateur Riders Club at Worli. My mother was a horse rider too. During their romance, they did a lot of horse riding in Gulmarg.

Dad was interested in fashion but he wasn’t a fashion victim. He liked wearing kurta pyjama, shirts and trousers and khadau (wooden sandals). He imbibed a lot from his trips to Switzerland and London and picked up stuff from there. There would be fabric brought home for curtains. And a week later, he’d be walking around in a shirt made of that material. That was him. Dad smoked a pipe and had a great collection of those too. He was fond of cat eye sunglasses. He loved cars and had a Chevrolet, a Mercedes, a Volkswagen and a Willy’s Jeep.

As an Actor

Dad was in the police force during the 1940s when he once went to watch a film at Metro cinema. There veteran filmmaker Sohrab Modi saw him and offered him a film. But he declined it. He eventually did Nausherwan-E-Adil (1957) with him. Later, he went on to do films like Mother India, Dil Apna Aur Preet Parayi and Dil Ek Mandir (between 1957-1963). His quintessential style emerged after Waqt (1965) and he came into his own with Kaajal, Humraaz and Neel Kamal in the late 60s. It was often said that he didn’t suit the romantic category. But look at him in Heer Raanjha, Lal Patthar and Pakeezah (early 70s). How much more romantic can you get? Personally, I liked him in Karmyogi, Bulandi, Police Public and Saudagar (between 1978- 1991).

We never went on his set. But we had once been for a vacation to Manali where dad had to shoot with Dilipsaab (Kumar) for Saudagar. The song Imlikabuta was being shot. We saw Dilipsaab and dad rehearsing the dance steps. My father was a horrendous dancer.

The Waining Years

I never saw him in dull spirits ever except during the last two years when illness got the better of him. Those were excruciating times. I’ve repressed those memories, it’s a defense mechanism. It began with Hodgkins, where you get lumps on the nodes. He underwent chemotherapy for that. He even shot for Police Public during those days. But the lumps recurred even more aggressively and reached the lungs and the bones in the rib cage. He refused to remain in hospital. He wanted to pass away peacefully at home. I left college in the US and came home to be with him. He passed away on July 3, 1996. The last conversation that I shared with him will remain with me forever. It’s too private to share. It’s difficult to watch his films in his absence. You hear his voice, you see him… it’s painful. The void is impossible to fill. I wish he had lived longer. Today, I’d love to have a man-to-man chat with him.