KILL THE BATS OR LIVE WITH BATS? THERE IS A THIRD OPTION EVEN DURING CORONAVIRUS CRISIS

Mumbai: What image comes to your mind when you think of bats? How we perceive certain animals depends on long-held beliefs, new information, their ecology and our experiences of them. Which is why, for many, the word ‘bat’ might conjure a not-so-flattering image of an upside-down, nocturnal species. For decades, people have associated fear and disgust with bats, and the Covid-19 pandemic has certainly not changed that image. Such perceptions have a bearing on conservation of bats and how we can coexist.

Largely neglected, bats are often associated with bad omen and misfortune across cultures. Interestingly, bats are also considered to be symbols of luck and happiness in some cultures, a prominent example being China. But with the virus threat, many in China are demanding that bats be expelled from human surroundings. Within India too, similar reactions, mostly misinformed and panic-driven, are being seen. The suggestion that the novel coronavirus or SARS-CoV-2 may have emerged from bats has put bat species at extra risk.

But did you know that, in some parts of India, people consider it a good omen if a bat enters a house? Literary references to bats are found in proverbs and folklore in many Indian languages. Few might know that emperor Ashoka’s fifth pillar edict (from the 3rd century BCE) enlisted bats as protected species.

I have been studying human-bat interactions for some time now, and am trying to understand why cultural values about bats range between extremes: from sacred to profane. Decoding this might help us understand the current situation better and foresee a future with bats. Do we let them be, or get rid of them, or learn to coexist?

Bats in India

Bats are an inseparable part of our surroundings — stand on a roof terrace at dusk in any Indian town or city, and 5 to 10 species of bats might be flying around. The only mammals capable of true flight, bats are the second most diverse mammalian group in India and globally, after rodents. There are broadly two groups of bats: insectivorous bats and fruit-eating bats. In India alone, there are 128 known bat species, of which 114 are insectivorous and the others are frugivorous or fruit bats.

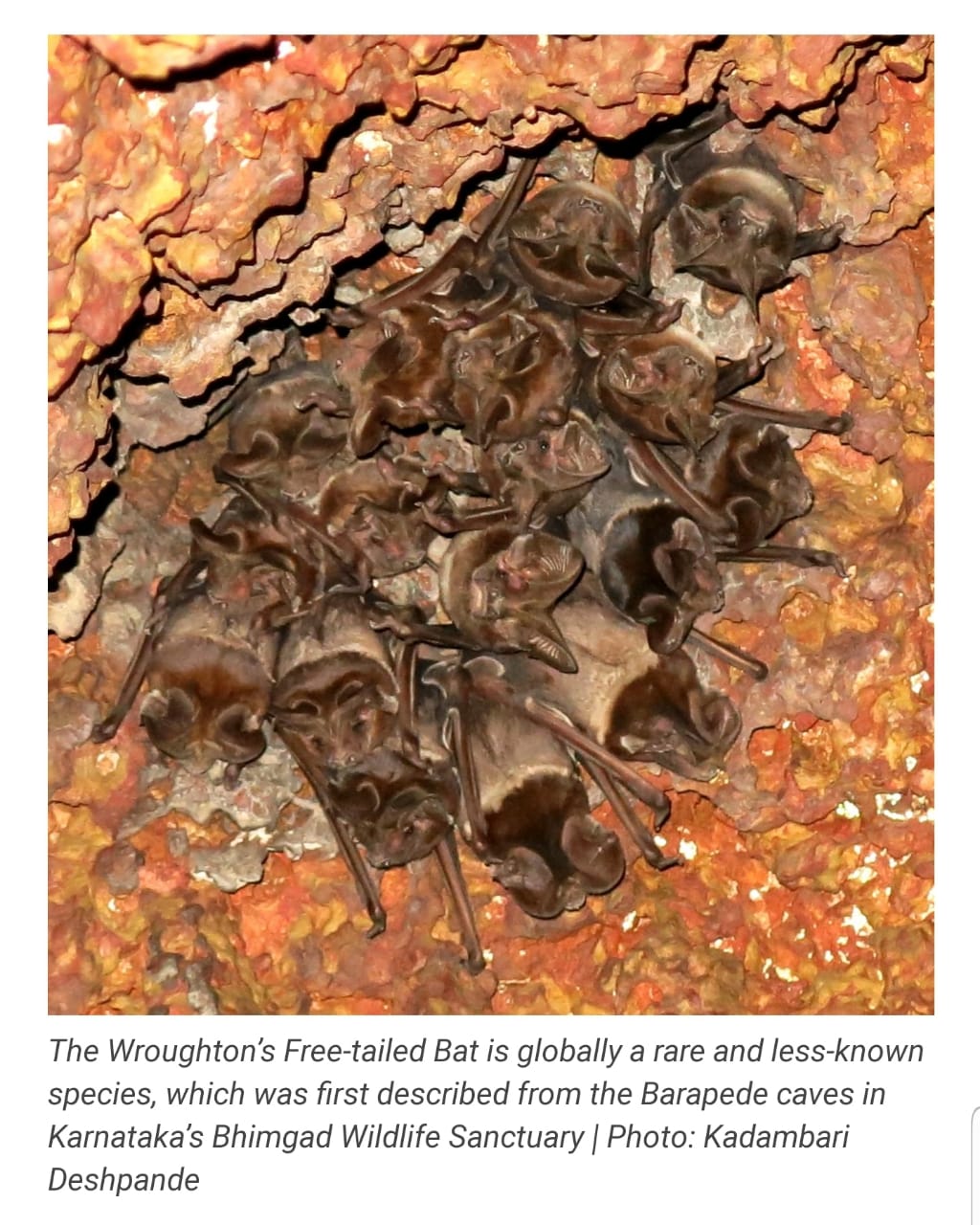

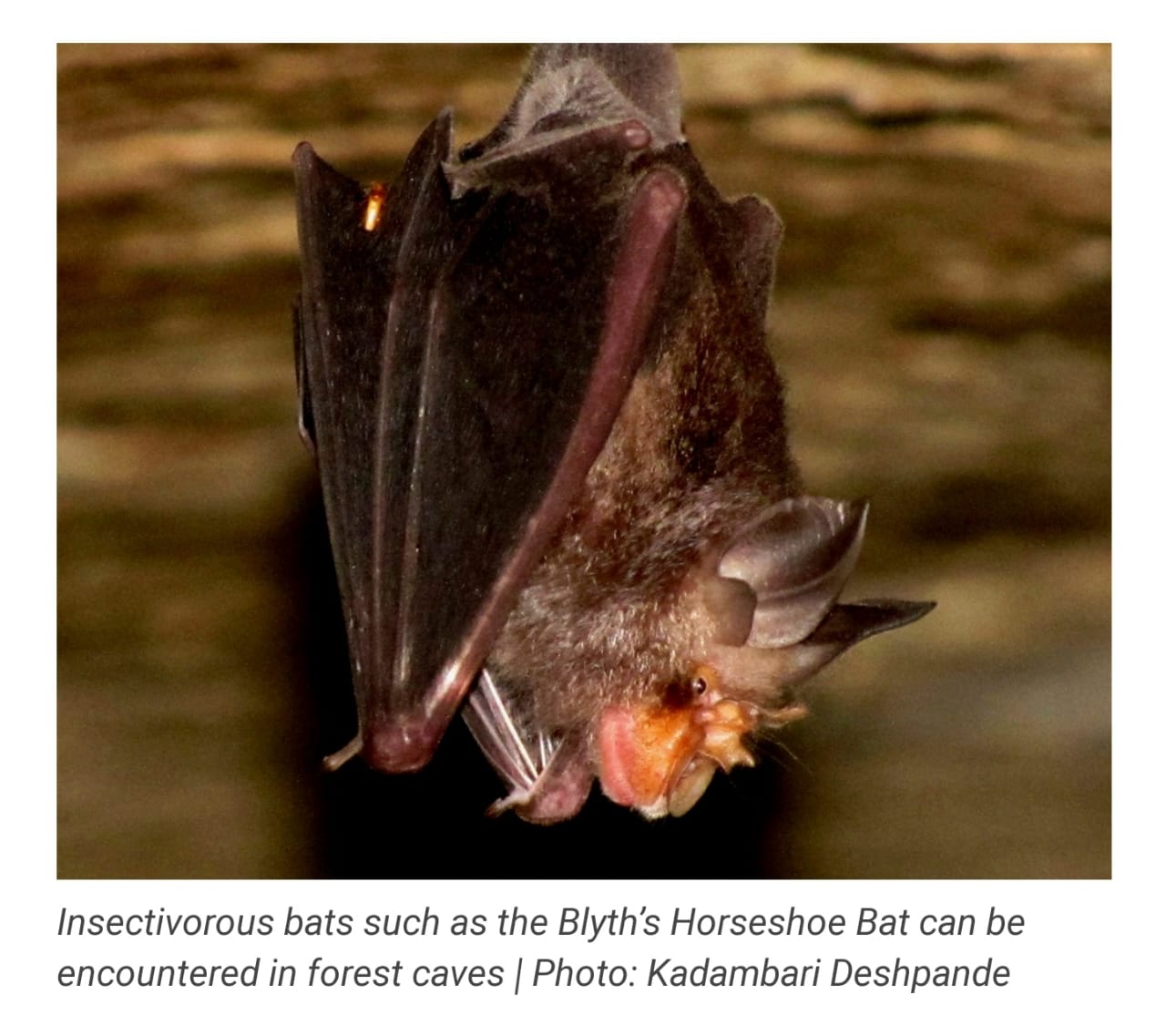

Insectivorous bats are the smaller of the two types and are specialised “echo-locators” that use ultrasound to catch insects. These bats are highly diverse, but poorly known. We see these bats in caves, tunnels, tree hollows, temples, old houses and abandoned structures. As there are so many insectivorous bat species, they stagger their aerospace use. For instance, free-tailed and sheath-tailed bats fly high in the open air, while evening bats (commonly seen Pipistrelles) fly mid-air. Horseshoe and leaf-nosed bats prefer foraging near vegetation close to the ground.

Insectivorous bats are the smaller of the two types and are specialised “echo-locators” that use ultrasound to catch insects. These bats are highly diverse, but poorly known. We see these bats in caves, tunnels, tree hollows, temples, old houses and abandoned structures. As there are so many insectivorous bat species, they stagger their aerospace use. For instance, free-tailed and sheath-tailed bats fly high in the open air, while evening bats (commonly seen Pipistrelles) fly mid-air. Horseshoe and leaf-nosed bats prefer foraging near vegetation close to the ground.

Fruit bats are the ones we see hanging on trees, or flying around Singapore cherry trees along urban avenues. The Indian Flying Fox is the largest of all, commonly seen in big numbers on tall trees, and perhaps the most familiar to us. Among the peninsular fruit bat species, the Salim Ali’s Fruit Bat is an endemic species, and lives only in evergreen rainforest pockets of the Western Ghats. The Fulvous Fruit Bat is found in caves, tunnels or even old temples, and can echolocate – a trait unique among fruit bats, which only rely on vision and smell to feed on fruits, pollen and nectar.

The Salim Ali’s Fruit Bat and the Wroughton’s Free-Tailed Bat are legally protected species in India. But unfortunately, all other fruit bats are listed as “vermin” in India’s wildlife protection law, while insectivorous bats do not find any mention in the law. News reports regarding putative linkages between bats and the COVID-19 pandemic have suddenly made bats the focus of strong reactions, even though they never got much attention before. To have or not have bats is now the big question.

Scenario 1: What if we just let bats be?

We often hear of appeals to just let bats be. It is a well-meaning argument, highlighting the importance of bats in the ecosystem. Many forest tree species that serve as a key food resource for wild animals are pollinated or dispersed by fruit bats. Not just forest trees, several commercial fruit crops also get propagated by bats. Insectivorous bats are important pest controllers in farms and their droppings are widely used as agricultural fertilisers.

Systems to harness benefits of bats have been widespread in India, as my own research has been showing. Commercially valuable fruits/nuts such as cashew and areca are dispersed far and wide by fruit bats. I found that people regularly tracked and collected these nuts from large bat roosts, and extracted stout profits due to bats. In Kerala, people even told me that seed aggregations by bats at feeding trees helped them reduce labour costs of seed collection.

Farmers across the world and in India also recognise the significance of bats in vanquishing pests in farms. Studies on pest control by bats (in the US and Southeast Asia) show that bats contribute to the food security of these areas. My preliminary studies have found that many insectivorous bat species feed on different insect pests in rice fields. Insectivorous bat guano (droppings) is used across India for its nutrient properties that enrich soil quality and improve yields of rice, other grains, sugarcane, and vegetable gardens.

Mathania chillies, a famous condiment of Rajasthani cuisine, are grown with bat guano brought from nearby caves. People believe that ‘bat soil’ gives Mathania chillies their distinctive red colour. Farmers across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra report similar uses of bat guano in agriculture. The dependence on bat guano, in some areas, seems to have even generated a sense of pride about bat roosts in the hearts of people, and these sites have been historically safe bat roosting places.

But this business-as-usual scene is not all rosy. One needs to objectively account for potential risks along with benefits of living with bats. In my experience, people living near forest areas show greater appreciation of services from fruit bats, but they also know the deal: fruit bats can damage mango, sapota, guava, or banana, to variable extents. Dealing with bat guano is not easy. Guano has a foul stench and acidic composition, and bat roosts in public places, tourist spots, pilgrimage sites, and buildings can impact these sites, and so are often vehemently disliked. Bats are consumed not only in China, as everyone wants to believe today, but also consumed for their meat and fat in many parts of India – rural and urban. Like collecting guano, bat hunting for meat and traditional medicine (believed to cure bronchitis and joint-pain) has been an age-old practice.

But this business-as-usual scene is not all rosy. One needs to objectively account for potential risks along with benefits of living with bats. In my experience, people living near forest areas show greater appreciation of services from fruit bats, but they also know the deal: fruit bats can damage mango, sapota, guava, or banana, to variable extents. Dealing with bat guano is not easy. Guano has a foul stench and acidic composition, and bat roosts in public places, tourist spots, pilgrimage sites, and buildings can impact these sites, and so are often vehemently disliked. Bats are consumed not only in China, as everyone wants to believe today, but also consumed for their meat and fat in many parts of India – rural and urban. Like collecting guano, bat hunting for meat and traditional medicine (believed to cure bronchitis and joint-pain) has been an age-old practice.

However, both fruit-eating and insectivorous bats are increasingly being recognised as hosts of potentially deadly viruses, and hunters, handlers or frequent visitors to bat roosts, including guano collectors, could be prone to disease exposure. Disease spread from bats to people is a rare occurrence, because many bat viruses need an intermediate animal host before they can jump to humans. This is still an emerging science, and there remain many unknowns about transmission pathways. Today, as we continue to harness bat benefits, we need to weigh them against these costs and risks.

Scenario 2: What if we just get rid of bats?

The Covid-19 pandemic has distressed people in India and other regions to the extent that people are demanding bat removal from their localities. Getting rid of bats may range from their ouster from roosting or foraging sites, to even mass culling. Bats, like other animals, also have an intrinsic right to live, but it may be difficult to convince anxious residents to let bats be just based on the rights’ argument. But then imagine what may happen if we actually cull bats en masse (irrespective of whether this can solve our current concerns). This will mean dealing with millions of individual bats of different kinds – a task impractical and unrealistic. Culling will be an enormous waste of time and money. Disposal of culled bats will be an even bigger challenge; careless handling and dumping of dead bats can seriously aggravate disease risks. A mass of culled bats could pose a bigger threat in terms of potential viral transmission than live bats would.

Culling bats would also result in huge ecological and economic losses to our crops and forests. Flowers pollinated by fruit bats open only at night. Many trees requiring long-distance seed dispersal for successful regeneration also need bats. But, the importance of bats is often not heeded. Recently, in Mauritius, mass culling of fruit bats was conducted before any systematic investigation of their actual damage to orchards. As a result of culling and ongoing habitat loss, the bat species became endangered in the 2018 IUCN Red List. It is thus critical that we first thoroughly investigate the actual effects of bats, before embarking on any such mission.

This holds true for insectivorous bats as well. Without them, our agricultural crops could face intense pest attacks. Other pest controllers might do the job to some extent, but bats can significantly control night pests that cause great damage to agriculture. In a 1984 article in Hornbill magazine, bat biologist Dr A. Gopalakrishna noted that “extermination of bat populations in the caves at Ellora and Ajanta was an added factor for the failure of the jowar crop in adjacent regions.”

Instead of culling, what if we just displaced bats from our neighbourhoods by disturbing them from their roosts? Here, we will simply be shifting ‘the problem’ elsewhere. Displaced bats will have to find new places to live in, and might overlap with more people in this search. “Centuries-old” roosts in the memories of elderly people indicate that bats show strong site-fidelity. Finding new roosts can stress bats out. It is well known that the potential to transmit viruses is greater in stressed bats. These arguments make it amply clear that culling, disturbing, or removing bats are unwelcome ideas. By doing so, we will not only nullify benefits from bats, but also amplify disease and pest risks.

Scenario 3: Can we learn to coexist with bats in a win-win situation?

Getting rid of bats is the wrong idea, but being happy with the business-as-usual scenario is not enough either. We need to do more to coexist with bats, safely and sustainably. This will involve careful, pre-emptive, and precautionary steps in the face of future uncertainties and risks: climate change, globalisation, and habitat loss from infrastructure development. Here, it will help to travel out of our urban confines and look at rural settings where people show greater adaptation to live with bats. Villages in Bihar and Odisha have been worshipping and protecting bats around them, even amidst the global crisis, and regard bats as their sentinels.

Most farmers I interviewed in villages along the Western Ghats say that fruit damage by bats is negligible, relative to their total farm production. Some farmers take a proactive approach to deter bats from orchards in a benign way: they hang compact discs (CDs) on trees, use lights, or thick nets to protect fruits. Farmers want bats around their houses because bats can function as free “mosquito-repellents”. To keep a shrine clean in Rajasthan, the simple solution found by the keeper was to collect the droppings of bats that roosted in the dome above the altar, in a cloth.

There are many examples, but we also must not romanticise: what people do is usually based on the historical continuity and utilitarian logic of these practices. It is also true that some farmers begrudge fruit bats and do not want them around. Old temples are frequently fumigated to get rid of bats. Not to forget that many villagers also hunt bats, and viral transmission is likely during pre-processing of hunted bats, even if not from cooked meat. Such direct interactions can put people at risk, and need to be minimised.

Here, the lack of mention of insectivorous bats, and status of fruit bats as “vermin” in India’s Wildlife Protection Act (1972) deserve to be revisited. Bats are mammals that live long with low breeding rates and so, bat populations remain within naturally regulated limits, unlike typical “vermin” species. Removing bats from the vermin list can not only contribute to preserving their important ecological functions and protect declining populations, but also help legally restrict direct contact of people hunting or disturbing bats. Positive interventions such as the Karnataka Forest Department’s recent appeal to the public to not hurt bats will receive a fillip if bats are legally protected.

But full protection to bats can be a double-edged sword. Removing bats from the vermin list does not imply that bats must be automatically given the highest level of legal protection. Protection priorities should also be graded for different species and populations of bats. In fact, strong legal protection measures can lead to antagonism in people, because inadvertent interactions with common bats may be tagged as “illegal”. Therefore, assigning an intermediate level of protection can help in keeping our options open in the conservation and adaptive management of bat populations, facilitated by ecological studies.

The ultimate indicator of successful bat conservation will have to be an aware society, and not just an increase in bat numbers. We need to educate ourselves by choosing the news we read carefully. A recent publication by Indian Council of Medical Research scientists showed evidence of bat-coronavirus in two species of fruit bats in India. This confirmation had no relation with virus strains involved in COVID-19, but news reports may have contributed to people complaining about bats and demanding action. Media-led miscommunication is a serious problem in such cases, which might cause panic in these sensitive times.

The ultimate indicator of successful bat conservation will have to be an aware society, and not just an increase in bat numbers. We need to educate ourselves by choosing the news we read carefully. A recent publication by Indian Council of Medical Research scientists showed evidence of bat-coronavirus in two species of fruit bats in India. This confirmation had no relation with virus strains involved in COVID-19, but news reports may have contributed to people complaining about bats and demanding action. Media-led miscommunication is a serious problem in such cases, which might cause panic in these sensitive times.

We need to make responsible and inclusive decisions for bats, with the right scientific knowledge. For one, bats do not deliberately or specifically harbour more viruses. A recent study confirms that it is the high diversity of bat species and evolution that makes their viral diversity proportionately higher among mammals. Free-ranging dogs on streets and rats in gutters, which we encounter more directly and frequently, also harbour dangerous viruses.

Finally, imbibing a culture of constructive management and safety precautions by people sharing space with bats is essential. The globally recognised One Health framework’s objective is to harmonise human health and wellbeing with bat conservation by identifying and avoiding disease transmission pathways. We can all inculcate such efforts at no extra costs, through basic safety precautions: covering our faces when we pass below bat roosts, not touching or eating fruits partly eaten by bats, minimising disturbance and stress to roosting bats. Farmers collecting bat guano or people handling electrocuted or dead bats must use gloves and masks. The same goes for bat researchers.

Such steps can gradually create systems that favour coexistence with bats at low risk and sustained benefits, without fear. But none of this will be adequate if we forget that we owe bats some empathy, respect, and a space of their own.

This article is a contribution on behalf of the Ecosystem Services Group, National Mission on Biodiversity and Human Well-being.

The author is a PhD candidate, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Bengaluru. Views are personal.