Clint Eastwood “Directing for most movie stars is a sometimes thing, and more often than not is a form of self-indulgence. For Clint Eastwood, directing was something he was determined to do from his earliest days as an actor, and something he now perhaps needs to do more urgently than he needs to act. Woody Allen aside, no star has directed more often than he has–20 films–or with greater professionalism of the old-fashioned kind, which specifically rejects pride of auteurship. He is always on budget and usually ahead of schedule. Actors love working with him because, being an actor himself, he allows them to find their own way with just the occasional, supportive suggestion.”

In the years since, Clint has directed just about every kind of movie–westerns, comedies, cop dramas, even a biopic–and it would be easy to categorize him simply as a genre director. But neither Pale Rider nor Unforgiving is a conventional western; Bronco Billy is unlike most contemporary comedies in both tone and topic; The Gauntlet, with its befuddled, loser hero, unlike most cop pictures; Bird, much darker, less celebratory and sentimental than most movie biographies of artists. Maybe Honky-tonk Man is a road picture, maybe at heart Heartbreak Ridge is a service comedy, White Hunter, Black Heart, a safari adventure, The Bridges of Madison County, an old-fashioned romance. But none fits neatly into a broad genre category.

Bird and Unforgiving are the most profoundly surprising and the most personal of his films. The former, a biography of Charlie Parker, the self-taught, self-destructive musician making his way up out of rural poverty to play his revolutionary music in the jazz clubs during the ‘40s and ‘50s, is Clint’s weightiest movie. At once compassionate and objective, the film provides a meditation on the life and work of an artist that the director, himself a self-taught musician and a passionate devotee of modern jazz, admired from the first moment he heard him in concert in 1946. It pays full tribute to the man’s genius and the sweetness of his spirit, yet offers no easy excuses or sentimental explanations for his suicidal behavior. Bird is ultimately as Clint sees it, a tragedy about a man refusing to take responsibility for himself and his gifts–a quality that often elicits Clint’s puzzled reflections, precisely because it is the opposite of his own way.

Bird and Unforgiving are the most profoundly surprising and the most personal of his films. The former, a biography of Charlie Parker, the self-taught, self-destructive musician making his way up out of rural poverty to play his revolutionary music in the jazz clubs during the ‘40s and ‘50s, is Clint’s weightiest movie. At once compassionate and objective, the film provides a meditation on the life and work of an artist that the director, himself a self-taught musician and a passionate devotee of modern jazz, admired from the first moment he heard him in concert in 1946. It pays full tribute to the man’s genius and the sweetness of his spirit, yet offers no easy excuses or sentimental explanations for his suicidal behavior. Bird is ultimately as Clint sees it, a tragedy about a man refusing to take responsibility for himself and his gifts–a quality that often elicits Clint’s puzzled reflections, precisely because it is the opposite of his own way.

Unforgiving can be read as a movie in which Clint acknowledges responsibility for certain aspects of his own life. In essence, it is a story about the ways that men drift into violence–through misunderstanding, through careless machismo, through misplaced pride and moral rigidity–and the costs, unacknowledged in most movies, including (as he said when he was making it) some of Clint’s own, of that behavior. It represents not an act of atonement, but rather a statement of self-awareness-brooding, ambiguous and, in the history of the western, quite singular in its immensity of emotion.

The first time he spoke lines to a camera, he blew them. A couple of pictures later he spoke his lines perfectly, but he was buried so deep in a dark scene that he couldn’t be seen. Toward the end of his first year as an actor, he had a nice little scene with a major star on a major production, and he found a good-looking pair of glasses that he thought gave him a bit of character. But Rock Hudson thought the same thing when he saw the kid wearing them, and Clint had to surrender his specs to the leading man.

Clint has never been given sufficient credit for the imaginative leap this undertaking represented, for the courage it required to willfully subvert his safe, boyish image of the time. By taking this long shot, he not only ended his long apprenticeship, he became a true rarity–an entirely self-made star.

Westerns

Westerns

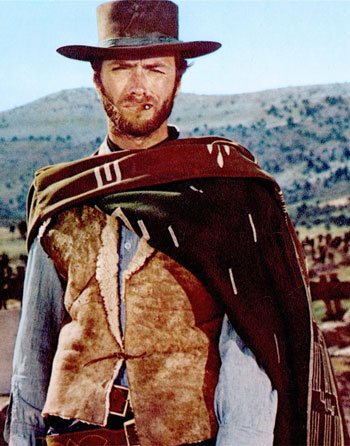

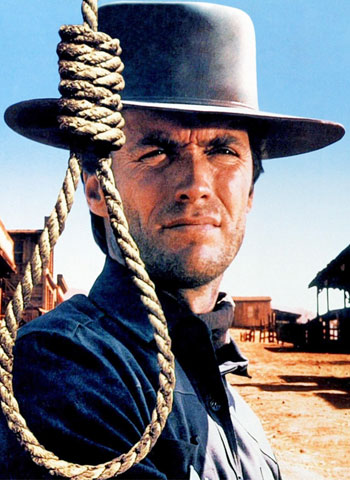

“I never considered myself a cowboy, because I wasn’t,” Clint Eastwood once said. “But I guess when I got into cowboy gear I looked enough like one to convince people that I was.”

When he went off to Italy to make A Fistful of Dollars, he was thinking “the western was in a dead place, encrusted with myth, poetry, stale pictorialism and simple moralizing.” The thing that drew him to this unlikely, low-paying project was the quality that earned it and his other Leone films so much disapproval when they first appeared–their straightforward, darkly comic insistence on the primitive and entirely ignoble nature of frontier life.

Clint Eastwood became a star in westerns, but he became a superstar playing cops. One can even identify the exact moment when it happened. It is early in Dirty Harry, when a gang tries to rob the bank across the street from Inspector Harry Callahan’s favorite hot dog stand. He looks up irritably as sirens sound, guns fire, cars start crashing. Then he strolls out into the street, still chewing his food as he unlimbers his .44 Magnum, wounds one of the miscreants and opens his immortal dialogue with the man (“I know what you’re thinking. Did he fire six shots or only five?”

Dirty Harry tapped into popular resentment of what many felt at the time was an excessive judicial concern for criminal rights. In those days, the liberal intellectual community felt that these protections, most famously expressed in the Miranda decision, had been late in coming and required defense against critics in law enforcement. When Dirty Harry appeared in 1971, the spirit of the sixties–generally anti-establishment, specifically anti-police–was still very much felt in the land.

But Kael gave him a bad, or at least excessive, rap. It is certainly true that Harry Callahan’s attempts to capture a psychopathic killer who is terrorizing San Francisco are constantly thwarted by a police bureaucracy bowing to liberal pressure and that he fails to observe all legal niceties in this case. Granted, Harry is not always–to put it mildly–careful in the way he expresses contempt for this caution, and he is not often delicate in his handling of suspects.

As we look back on the film almost a quarter century later, we see two things: that at every level of society sympathy has switched decisively toward victim rights and away from criminal rights, which makes Harry Callahan look almost like a prophet; and that the violence of the movie, also much criticized at the time, looks mild in comparison to the preposterous firepower now routinely released in urban action films (Die Hard or Lethal Weapon films or almost anything starring Sylvester Stallone).

As we look back on the film almost a quarter century later, we see two things: that at every level of society sympathy has switched decisively toward victim rights and away from criminal rights, which makes Harry Callahan look almost like a prophet; and that the violence of the movie, also much criticized at the time, looks mild in comparison to the preposterous firepower now routinely released in urban action films (Die Hard or Lethal Weapon films or almost anything starring Sylvester Stallone).

Clint Eastwood understood this character. He had been raised in blue-collar Oakland, across the bay from San Francisco, gone to a trade and technical high school, knew (and continued to respect) working-class people–their virtues, their frustrations, their outrages. Ultimately, that is what he thought this movie and all the Dirty Harry movies were most essentially about. And the other cops he has played–whether it was the drunken loser Ben Shockley in The Gauntlet or the sexually confused Wes Block in Tightrope–partook of these same characteristics. They were never smooth guys, or articulate guys. They weren’t even too smart. They just had good, sound instincts. These figures flattered them with understanding, but never toadied to them. Or talked down to them. No wonder Clint’s audience could never get enough of them.

Man of Action

“I’ve never thought of myself as a leading man,” Clint Eastwood once said, somewhat surprisingly, “though I guess at one time I was considered one… being one of the young guys bopping’ around town on a television series. But I always tried to be a character actor even then.”

Maintaining this identity was hard for Clint-casting directors couldn’t see beyond his good looks. Later, when he had established himself with Rawhide and the spaghetti westerns, agents and studio bosses wanted him to play straightforward heroic leads. That’s where the money is, after all. For a time, he obliged them–with Where Eagles Dare, Kelly’s Heroes, and The Eiger Sanction–though he always alternated these big pictures with smaller, anti-heroic ventures like The Beguiled and Play Misty for me (the first film he directed).

The more expensive, expansive films fulfilled their function of helping to establish Clint’s credentials as a star that could carry a big movie. Yet he always seems shy, almost self-effacing in these contexts, an actor is more serious about his craft than he sometimes chooses to let on, in search of an author who will be capable of giving him a real character to play. These movies–among which one should probably list Joshua Logan’s action less but pricey musical, Paint Your Wagon–wear poorly precisely because they do not intelligently count the costs of heroism, of machismo, if you will. This is a subject that deeply interests Clint Eastwood, though it is not something he talks about much. But in these pictures, it is just an unexamined premise.

The more expensive, expansive films fulfilled their function of helping to establish Clint’s credentials as a star that could carry a big movie. Yet he always seems shy, almost self-effacing in these contexts, an actor is more serious about his craft than he sometimes chooses to let on, in search of an author who will be capable of giving him a real character to play. These movies–among which one should probably list Joshua Logan’s action less but pricey musical, Paint Your Wagon–wear poorly precisely because they do not intelligently count the costs of heroism, of machismo, if you will. This is a subject that deeply interests Clint Eastwood, though it is not something he talks about much. But in these pictures, it is just an unexamined premise.

Clint meant to look into this matter more deeply in his own Firefox, but plot and special effects largely overrode his efforts. He did much better a little later with Heartbreak Ridge, which raucously, yet poignantly, asks what a lifelong soldier is supposed to do when he gets too old to fight in wars that are increasingly meaningless anyway. The same is true of White Hunter, Black Heart, in which a macho movie director must reexamine the noisy, careless audacity by which he has lived his life and managed his career. In these movies, the character actor has real characters to play–characters that in some ways subvert, or at  least cause us to question, common (and superficial) assumptions about Clint Eastwood’s image. In his mind he has never been an action star any more than he has been a leading man, and without talking about it directly, he would like us to understand that.

least cause us to question, common (and superficial) assumptions about Clint Eastwood’s image. In his mind he has never been an action star any more than he has been a leading man, and without talking about it directly, he would like us to understand that.

Back roads & Barrooms

Not in grown-up life, certainly. But as a child of the Depression, he was obliged to move about constantly as his father looked for work–most of it marginal–all over California. As a young man trying to find himself, Clint spent a couple of years drifting around, doing hard manual labor-lumberjacking, working in steel mills and aircraft factories. Moreover, his lifelong passion for jazz drew him at an early age into the low dives where the music he loved was played. All of this did not give him the sympathetic sense of working-class life, patronizing nor indulgent, that marks some of his best, and possibly most enduring, work.