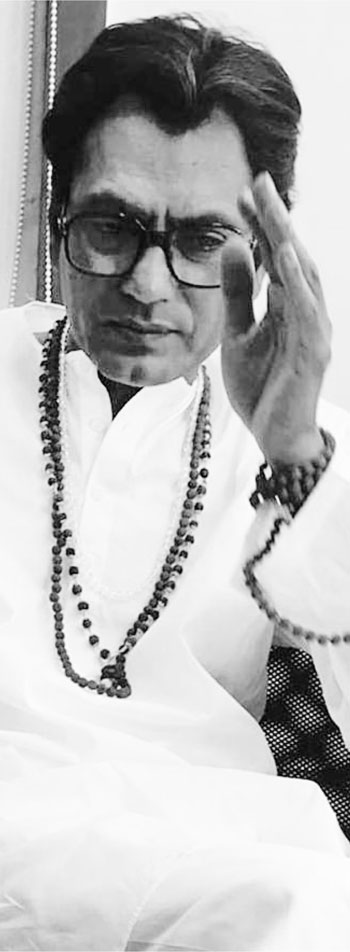

Nawazuddin Siddiqui : The irony of Nawazuddin Siddiqui, the success that he has become ineluctable.

The one man army can easily be considered as one of the most poignant factors, and figures, playing a pivotal role in sweeping off the ‘stardom’ concept from the surface of the Hindi film industry.

Did the irony of an outsider from Uttar Pradesh playing Bal Thackeray in his biopic strike you when you accepted the role?

No, nothing like that. It’s simple as I am an actor and they thought Nawaz would do justice to this part. And as actor, to do a role like this is a huge opportunity – not just me, but any actor. It is a lot of hard work, but it also gives you joy.

It’s given that the movie is being made by the Shiv Sena, did you consider that it might show the subject only in a positive light?

I didn’t think of all these things at all. Sanjay Raut, who has written the story, is also a journalist. The entire Thackeray family is made up of artists – someone was a cartoonist, someone an artist. They have art in their blood.

Before you did the film, what was your opinion of Bal Thackeray and has it changed since you played his role?

Before you did the film, what was your opinion of Bal Thackeray and has it changed since you played his role?

I have never met him, but had read a few of his interviews. He’s always been controversial, that is a fact. But he was also one of those personalities that you could either hate or love. You could never ignore him. You could say what you want about him, but when millions of workers lost their jobs in the mill strike, he worked for their welfare. A lot of things we see in practice now, he started. He encouraged the Marathi youth to be entrepreneurs. All these big hospitals we see, he gave land for that, built highways. We will show all these things in the film.

As an actor, does your ideology influence your work at all?

I don’t have any ideology or philosophy. I am a professional actor. When I played Manto, I was him. Just because I am playing a gangster, it doesn’t mean I will be Ganesh Gaitonde (his character from the Netflix series “Sacred Games”) all the time. It is a period in time, till you are doing the film, because you have to do justice to the film. But you also have to get out of it once you finish the film, because then you have to immerse yourself in another role.

We are seeing a lot of political films being made nowadays. How do you see this trend?

In the past, we have made films with problematic themes which we have long accepted. Like the fake characters, the sarv-gunn-sampanna (near perfect) hero, who can do no wrong. He’s eve-teasing the heroine, but we accept that and make such films into (box office) hits. It is our hypocrisy that we want to see no flaws in the hero, but then say that biopics glorify their subjects. That is because the audience doesn’t want to see hardcore reality, like the one shown in “Raman Raghav 2.0” and “Manto”. They run away from it.

As an actor, what are you searching for now?

What am I searching for now…. (trails off). When I was in NSD (National School of Drama), we were only told one thing – try and find yourself. I am doing that, with every character, and this is a never-ending process. With every film, you start that process all over again. What fascinates me most is that during that process, you are in the middle of a scene and you have an epiphany about yourself. That is what is fascinating for me, rather than staying satisfied in my success and the knowledge that people will say good things about my performance anyway. I don’t want that corruption in my art. I will continue to do the kind of films that teach me something about myself, whether they work at the box office or not, because that is my personal journey.

What do you focus most on during a performance?

Whether I am playing Thackeray or Manto or Ganesh Gaitonde, I am always worried about how honest I am being in that scene. An actor’s biggest worry is that it shouldn’t be mimicry or caricaturish. Am I real enough in this or not? I obsess about this all the time, and it messes with my brain, honestly.

Are you able to judge your performances objectively?

Absolutely. When you watch it, you know where you’ve made mistakes, where you’ve missed steps. Thankfully, no one else notices and they praise your performance, but you always know. Everyone knows their weaknesses.

What about your strengths? Are those clear to you as well?

What about your strengths? Are those clear to you as well?

Honestly, I can never see my strengths. Never. I am always jittery and nervous before I start a new role and I feel that I have escaped, because no one else has noticed the flaws in my performance. Only I know how I fight those weaknesses.

Have I managed to achieve what I had visualized about this character and this role?

At night, before sleeping, I tell myself, “Oh, I’ll crack this scene!”. But when you face the camera the next day and there is chaos and a hundred people around you, there are scores of obstacles between you and achieving that nirvana – the perfection that you had visualized. Those who did achieve nirvana, they asked questions to themselves and went away to the mountains to find those answers.

I want those answers too, but I have to stay here, in this material world, in a crowd and try and find that elusive nirvana.

Does this professional struggle intrude into your personal space? Or are you able to segregate the two?

It happens many times that while shooting, you lose sense of who you are. That only happens if you don’t have any ideology of your own. You have to be like water, which takes the shape of whatever you pour it into. That can only happen if you don’t have any philosophy of your own.

How is that possible? You have a thought process and a way of thinking.

You are right, and it is a weakness of mine. I am so affected by all the characters I have played that I have no opinions of my own. As an actor that is a good thing, but as a person, perhaps not. It is a weakness.

Acting is a collaborative process. Have you found collaborators who share the same wavelength? Or has that also been a process of adjustment?

No, you have to adjust. My own style of acting is very internalized. When I am doing a role, I want that I be judged not for what I am doing on the outside, but what is going on in the character’s mind. What’s in my head may not manifest in my expressions or in my eyes, but you should be so capable as an actor that the audience should be able to tell what you are thinking. I believe in that kind of cinema, but our cinema is still far away from that level. Hopefully with younger filmmakers, that will change.

From a village in UP to Bollywood. What’s your story?

I belong to a family of farmers. We are based in this village called B-U-D-H-A-N-A, in district Muzaffarnagar of Uttar Pradesh. There wasn’t much scope for education there. But somehow my siblings (7 brothers and 2 sisters) and I managed to study. In my village only three things work: gehu (wheat), ganna (sugarcane) aur gun. The fear this gun culture instilled made us move out from our village.

It was much later that I started taking interest in theatre. After completing my studies, I took up jobs like that of a chief chemist in Baroda. Then I joined a theatre group in Delhi. Since there is no money in theatre I had to take up a job as a watchman. All these things happened simultaneously. Then I enrolled myself in the National School of Drama (NSD), passing out in 1996. I worked in Delhi for four years before finally moving to Mumbai in 2000.

How did Mumbai treat you?

How did Mumbai treat you?

Delhi had drained me financially. In the beginning I felt it would be easy to get work here. But that didn’t happenFor 4-5 years I did a lot of small roles crowd, scenes. Around this time cinema was taking a turn for the better. Directors like Anurag Kashyap were making films like Black Friday. Slowly I started getting work. In the past 3-4 years I’ve done some 9 films which have me in important, central characters.

Do your folks watch your films? Do they support your choice of profession?

My parents live in the village where there are no theatres. Films are screened in the district, Muzaffarnagar, which is 40km from the village. They have to travel the distance to watch me. There’s nobody to question who’s doing what. As long as I am doing some work and doing it well, they have no problem.

Now that you’re popular here, how do your friends and relatives react when you go home?

It’s a sense of satisfaction because I proved all of them wrong. All of them said ‘kya hero banega (how will he become a hero)’ when I set out. When I go back now they say ‘isne toh karke dikhaya (he has done it)’. I made it possible.