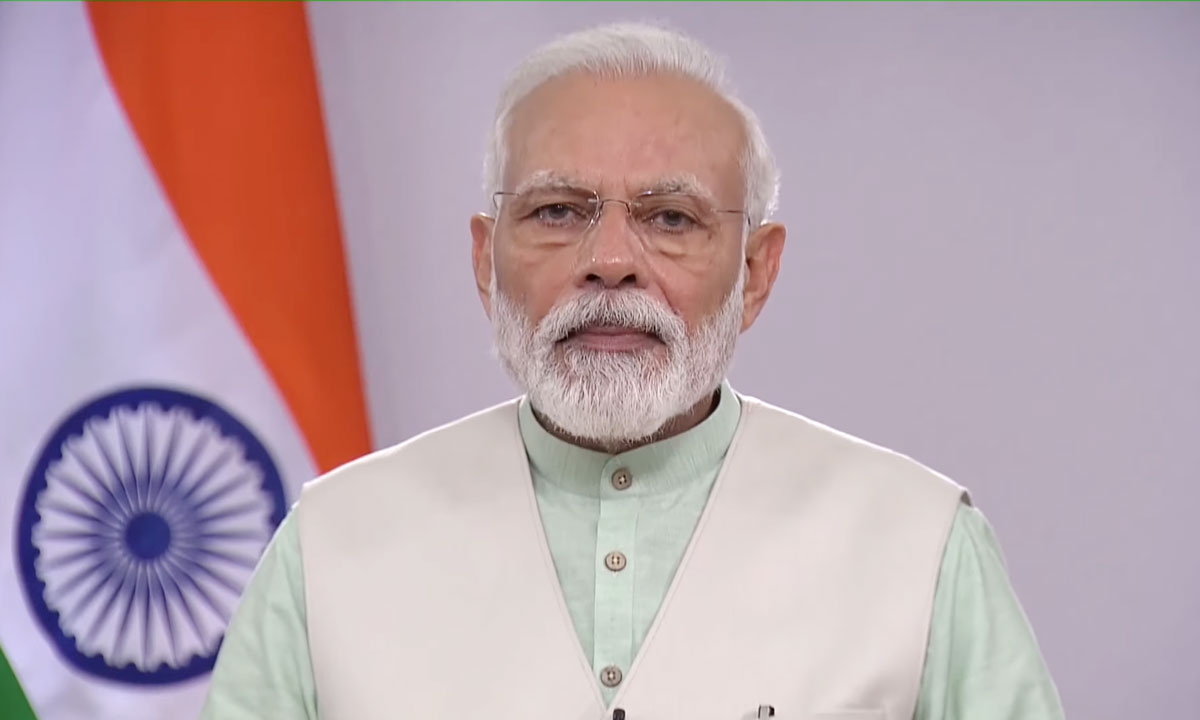

PM Modi Lockdown Failed, Even After Invoking “The Disaster Management Act” Extraordinary Powers To Issue Sweeping Orders To All The States

The Big Story:

We look at what the government claims the lockdown achieved and what that means for India going forward.

India was given 4 hours’ notice before going into a national lockdown on March 25 for an intended three weeks. The restrictions were eventually extended until May 31, though some relaxations kicked in on May 4 and a much larger re-opening was permitted from May 17.

Starting May 25, domestic flights will resume. From June 1, the Indian Railways will go back to running hundreds of regular trains every day. In many cities – with the hard-hit Mumbai being a major exception – taxis, auto-rickshaws and buses are back on the roads, and workers are back in offices, factories and construction sites.

This is good news for the Indian economy, which has been devastated by one of the world’s harshest lockdowns. But it also comes with fears that the number of Covid-19 cases might suddenly jump, with people out and about again.

As we’ve noted from the very beginning, a significant aspect of India’s coronavirus lockdown is that it was “early”, meaning it was put in place when there were only around 500 confirmed cases and only 10 people had officially died of the disease.

This undoubtedly helped reduce transmission, ensuring that India did not experience a rise in case counts similar to those in countries like Italy, France and Spain. But we also noted that India’s short-notice lockdown would bring up two problems:

A severe lack of preparation, since the government had not built the state capacity to handle the public’s needs during lockdown.

The likelihood that India would have a harder time estimating when it is likely to see a peak in new cases, forcing the country to emerge from lockdown even as its Covid-19 growth rate remained high.

Both of these have ended up coming true.

The lack of planning for the lockdown led to the massive migrant crisis. (Read Supriya Sharma’s summary of the policy-making disaster here). Now, India is opening up without having passed a peak in new cases, which has been one of the parameters for many other countries to move towards re-opening.

We wrote about some of these indicators when Lockdown 3.0 was ending, earlier in May.

There are, of course, no easy choices when it comes to pandemic policy-making. Yet two questions are beginning to be asked even louder now.

There are, of course, no easy choices when it comes to pandemic policy-making. Yet two questions are beginning to be asked even louder now.

Did India move too quickly to lock down? And, more importantly, has India squandered its lockdown?

Lockdown successes

Over the last week, as questions about India’s Covid-19 response continued to grow, the government made a concerted effort to claim that its lockdown was a success.

“There are reports in a section of the media about some decisions of the government regarding the lockdown implementation and response to COVID-19 management,” said a ministry of health press release that offers a mixed-bag of data points on what was achieved during the lockdown

– such as the number of beds in dedicated Covid-19 hospitals and an increase in domestic production of protective equipment and masks.

On Friday, the Health Ministry held a press conference to drive this point home.

Ultimately, this was the TL;DR number of how many Covid-19 cases and it wanted people to see, based on 5 different models:

Ultimately, this was the TL;DR number of how many Covid-19 cases and it wanted people to see, based on 5 different models:

It says that there would have been 14 lakh to 29 lakh (1.4 million to 2.9 million) more cases in India if it hadn’t locked down, and between 37,000 to 78,000 more deaths.

It says that there would have been 14 lakh to 29 lakh (1.4 million to 2.9 million) more cases in India if it hadn’t locked down, and between 37,000 to 78,000 more deaths.

The full briefing with lots of other data points to dig into is here.

Though this may not be attributable to the lockdown per se, and be heavily skewed by the way in which countries are collecting data, the low rate of deaths in comparison to confirmed cases is one of the features that remains significant about the pandemic in India.

Testing Trouble

Testing Trouble

Before engaging with those numbers any further, it is important to add the caveat that testing rates and approaches are not uniform across countries. Of the countries with the largest number of Covid-19 cases, India has among the lowest rates of testing per 1,000 people.

We have told you in the past how the government botched up the procurement of rapid testing kits from China. This meant that India could not move forward with plans to get a sense of how many people in the wider population have been infected. The Indian Council for Medical Research has now developed a new rapid testing kit, but there are questions about how reliable these will be as well.

We have told you in the past how the government botched up the procurement of rapid testing kits from China. This meant that India could not move forward with plans to get a sense of how many people in the wider population have been infected. The Indian Council for Medical Research has now developed a new rapid testing kit, but there are questions about how reliable these will be as well.

A study in the Economic and Political Weekly, meanwhile, pointed to the very close correlation between an increase in number of tests and an increase in number of confirmed positive cases. That might seem obvious, but the other potential outcome would have told us that India is doing a good job of tracking the spread of the disease – an increase in testing not correlating to an increase in confirmed cases.

Unfortunately, the data makes it clear that if we simply looked for more cases, i.e. tested more people, we would find them.

That is exactly what happened in Gujarat where a special drive to detect infections among those who were most likely to come into contact with people during the lockdown – grocery shop owners, vegetable sellers and garbage collectors – led to a big spike in the number of confirmed cases.

This is important because as people emerge from the lockdown, the best way to handle the spread of the disease will be for India to be able to trace those who have it, whether they have symptoms or not, and isolate them so that it doesn’t spread. This approach, however, depends on widespread testing.

The Indian Express reported that more than two-thirds of the 630 districts that have had at least one case of the disease do not have a Covid-19 lab. This could end up being a bottleneck, particularly as the disease spreads into eastern states that have fewer labs and patchier healthcare networks.

Out of Ammo

One hard-to-answer question that ought to follow the government’s big presentation on the success of the lockdown is whether the gains were sufficient enough to justify the massive economic distress and the humanitarian crisis that followed.

Or, to put differently, if the government had waited longer to design a more nuanced lockdown with better planning for migrants and the hit to the economy, would it have been even more effective? The reason it is hard to answer is because this depends too much on hindsight and assumptions about state capacity, even if the lack of forethought when it came to migrant workers is all too apparent.

A more tangible concern may be this: all those numbers undoubtedly show that India’s draconian lockdown – among the world’s harshest – had a massive effect on the spread of the virus, and yet they still did not push India past a peak and onto a downward trend as it did in other countries.

As Agency pointed out, “Although India reported its first case on January 30, around 74% of India’s total cases have been reported in May alone.”

“Lockdown slowed down the transmission a bit in some parts of India but in most big cities, the transmission is happening quickly,” said epidemiologist Jayaprakash Muliyil, who is part of the research group assisting the National Task Force on Covid-19 and has been against a lockdown approach from the very beginning.

“Lockdown slowed down the transmission a bit in some parts of India but in most big cities, the transmission is happening quickly,” said epidemiologist Jayaprakash Muliyil, who is part of the research group assisting the National Task Force on Covid-19 and has been against a lockdown approach from the very beginning.

“Now if you say there is no community transmission that will be a falsehood,” he added. For the record, India insists there is no community transmission yet, a claim that appears mostly meaningless when the country has more than 138,000 total cases.

What’s worse, the long lockdown – and resulting distress – may have destroyed the capacity and willingness of Indians to go into lockdown again. This has not been helped by public messaging that the lockdown itself (just like the Janata curfew before it) will kill the virus, instead of just being a pause button.

From the very beginning it was suggested that a waxing-and-waning of movement restrictions would be needed to keep the healthcare system from being overwhelmed, at least until a vaccine is widely available or the population has gained herd immunity (meaning that the majority of people are immune because they caught the virus in the past).

Across the board, most experts seem to believe that India – already among the top 10 in number of cases globally – will continue to see numbers increase until they hit a peak some time between late June and early August.

But, having seen the government unable to handle situations like the migrant crisis and unwilling to spend money to restore economic demand, will Indians be willing to go back into lockdown if cases around them are spiking?

Has India spent all of its ammunition in the first two months, and will now have to simply live with the virus, as many policymakers have been intent on repeating? Or has the lockdown actually helped to condition Indians into implementing physical distancing, even as the health preparedness claimed by the government means the systems are ready to handle the inevitable spikes?

Here is what VK Paul, the chairman of the National Task Force on Covid-19 said in the press briefing when asked about what the numbers will look like going forward.

“Real growth trajectory of the novel coronavirus depends not only on the mathematics of the spread of infection, but also on behaviour of community and society. How we respond cannot be put into a model/equation, we can only make some guesses. Hence it is difficult to predict. Some epidemiologists however estimate high numbers as well. However, we have not done this estimate. What we have to say is that we will take required actions and control the infection to the maximum extent possible.”

Flotsam and Jetsam

Cyclone Amphan, the most destructive storm in living memory that formed in the Bay of Bengal, hit India’s east coast on Wednesday, killing at least 86 people, wiping out thousands of homes and leaving many cities without electricity or phone connections.

India spent the week battling neighbours on several fronts: the Army has had face-offs with Chinese soldiers long the Line of Actual Control in many places, ratcheting up tensions between the two nuclear-armed nations. In addition, Nepal’s Prime Minister referred to Covid-19 as the “Indian virus”, even his administration squabbles with New Delhi over the exact boundaries between the two countries on official maps.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath’s administration pulled out all the bureaucratic tricks to prevent the entry of hundreds of buses arranged by the Congress that were going to be used to drive migrants home.

The Union government suddenly announced the resumption of domestic flight services, reportedly after airlines said they were facing bankruptcy, but it has faced pushback from a number of states worried about the disease continuing to spread.